Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Vino Studio/Nineteen57 Events

Vino Studio/Nineteen57 Events33-year-old model and author Abena Christine Jon’el’s recent appearance at a major fashion show in Ghana is not to be missed.

Walking down the catwalk wearing a colorful African print prosthetic leg, she impressed with her look.

The Ghanaian-American wanted to make a statement on the visibility of people with disabilities, building on years of work speaking out on the issue in the United States and Ghana.

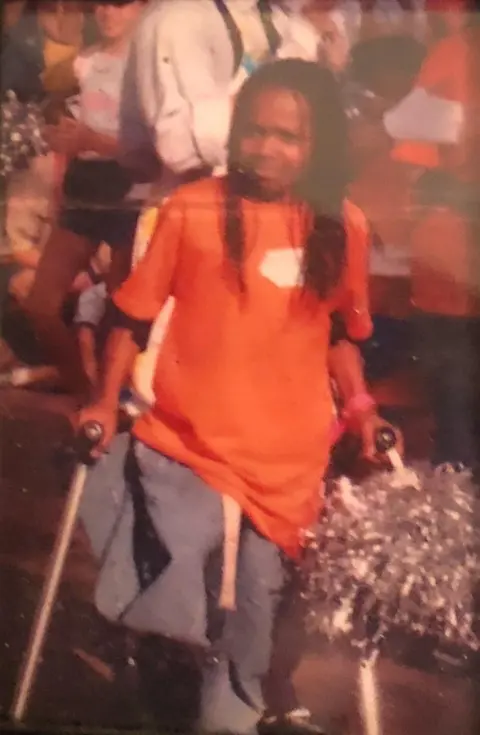

At the age of two, Abena’s life began to face challenges that most adults would find difficult to face.

A large tumor appeared on her right calf, the first sign of rhabdomyosarcoma, a rare and aggressive soft tissue cancer. Doctors presented her mother with a difficult choice: Radiation therapy, which could leave her wheelchair-dependent, or amputation. Her mother chose the latter.

Speaking to the BBC today in a restaurant in Ghana’s capital Accra, surrounded by friends and family, Abena said without hesitation: “It was the best decision she could have made.”

She now lives in Ghana but grew up in Chicago, USA.

Even before she understood what cancer was, her early life was shaped by treatment and recovery. Exercise became a way to measure survival and rebuild confidence. In a way, it’s taking over a body that’s been through so much.

Abena Christine Jonel

Abena Christine JonelBut when she talks about her youth, it’s not the clichéd story of an inspirational disabled child sometimes presented in glossy campaigns: a conformist bravely but silently triumphing over adversity.

She completely rejects this stereotype.

“People imagine kids with disabilities as straight-A students who are cute, quiet, and perfect,” she said.

“I was the exact opposite. I was loud, I was a little black girl running around on one leg, I didn’t let anyone push me, and I struggled in school.”

Her disability does not soften her character but rather sharpens it.

This sharpness, which she now jokingly describes as her “professionally inspiring” energy, was something that would carry her with her throughout her life.

In the United States, she worked as a writer—first as a poet—and then as a public speaker, talking about her life experiences in the hope of inspiring people.

She wants people to see what she has achieved and “let me hold up a mirror so you can see yourself and what you can achieve if you believe”.

Long before she ventured into public speaking or modeling, Abena felt a pull to Africa that she couldn’t express but couldn’t ignore.

As a young person in the United States, she immersed herself in books about the history of Africa before colonialism, especially West Africa. The more she read, the stronger the attraction became.

But her first visit to Ghana in 2021 changed everything.

Abena Christine Jonel

Abena Christine JonelIn Ghana’s central region, standing at the site of the Assin Manso Slave River – where slaves were sold before traveling some 40 kilometers (25 miles) south to the coast – she experienced what she describes as “a moment that rearranged my entire understanding of myself.”

The weight of history meets the weight of belonging, creating a sense of identity she never had when growing up in America.

Upon her return, she fell into a deep depression.

“It felt like I had finally found a missing part of myself in Ghana,” she said. “Leaving felt like being torn from where my soul belonged.”

Three months later, she packed her bags and moved permanently.

Garner embraced her in a way she still can’t describe.

“I am Ghanaian by blood and adoption,” she says proudly.

During the four years she lived in Accra, Ghanaians treated her in a way that only Ghana knew: with warmth, teasing, family and a name. She now lives with a Ghanaian mother, who introduces her as her daughter.

“My Ghanaian identity is not fake,” she said. “This is not role-playing. This is ancestral. As Kwame Nkrumah said: ‘I am not African because I was born in Africa, but because Africa was born in me.’ That’s what Ghana means to me.”

Her prosthetic leg itself is this declaration of love.

Wrapped in kente cloth, it serves as both a cultural symbol and a mobility aid.

“It has always been and always will be Kent,” she said. “It represents my love for this country, its heritage and its pride.”

Living with a disability in Ghana brought a new purpose to her life, one that went far beyond personal expression.

For Abena, the difference in how people with disabilities are treated in the United States and Ghana comes down to visibility and accessibility.

“In America, progress is happening, slowly and imperfectly, but it’s happening. People with disabilities are being invited into more spaces,” she explains. “It’s still ableist, but at least there’s someone trying to change the narrative.”

Ghana is still at the beginning of this journey, she said. Not because of a lack of compassion, but because of a lack of representation.

After relocating, she continued to speak out for the rights of people with disabilities.

“Disabled people are not widely represented in a positive light in Ghana,” she said. “So shame breeds. Negativity breeds. People don’t see us in a position of strength or beauty or joy, they only see us in a struggle.”

Her advocacy is based on changing that perception. Not out of pity, but out of visibility.

With Kent’s prosthetics, unfiltered personality and refusal to shrink herself to fit public expectations, Abena wants Ghanaians to see people with disabilities for who they are: ambitious, stylish, talented, complex, proud and human.

“A disability is not a limitation. Being disabled does not mean you are disabled,” she said.

“Lack of support, lack of accessibility, that’s what’s holding you back.”

Abena Christine Jonel

Abena Christine JonelHer advocacy found a new stage at the 15th edition of Rhythms on the Runway, one of Africa’s most prestigious annual fashion shows, held last month at Accra’s historic Osu Castle.

During preparations for the show, Abena contacted the organizers directly.

She knows what her presence means, not just to herself, but to Ghana. She wants to open the door to a different form of representation and force the country to have a conversation that has been delayed for too long.

“I know this will be a landmark moment for Rhythms on the Runway and for Ghana,” she said. “If I want inclusivity in this industry, I have to be willing to take the first step.”

She did it.

As she walked confidently down the runway, draped in fabric, her prosthetics shimmered in the spotlight and the entire room transformed. What happened next became one of the most talked about moments of the night.

“Her strength shines through,” said Abla Dzifa Gomashie, minister of tourism, culture and the arts. “‘I have different abilities and I’ve done it.'”

Show organizer Shirley Emma Tibilla said: “Her walk was more than just a performance, it was a powerful affirmation of talent, beauty and confidence that knows no bounds. We are proud to provide a platform where her light can shine so boldly.”

“Abena’s presence is absolutely powerful. It’s about true inclusivity, celebrating every story, every person and every ability,” added Danta Amoateng, entrepreneur and founder of the Cuban Diaspora Investment Awards.

But for Abena, the night was not about the applause. That’s the message. That night, people with disabilities were not just spectators, they were center stage.

Standing at the intersection of identity, disability, tradition and fashion, Abena represents a new way forward for Ghana, where inclusivity is not quietly suggested but boldly demanded.

Her journey from a two-year-old cancer patient to a woman reshaping how Ghana views disability is not a story of survival but of renewal.

She reclaimed her identity, her mobility, her sense of belonging, and her place in a country that, in her words, “fought for me before I even set foot here.”

Her work is far from done. But whether she’s on the runway, behind a microphone, or mentoring young amputees, one thing remains constant, she refuses to dim the lights. She also refuses to let others like her be overshadowed.

“Ghana is my home,” she said.

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC