Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images“Want to experience the royal charm of Jaipur? Don’t come here, just buy a postcard,” quipped a local taxi driver during my recent visit to this northwestern Indian city.

I asked him why the amber capital of Rajasthan, which attracts tourists with its palatial palaces and majestic forts, looked so crumbling.

His answer reflected despair at the urban decay that plagues not just Jaipur but many Indian cities: traffic jams, stale air, strewn with piles of uncensored garbage and indifference to the remnants of its glorious heritage.

In Jaipur you’ll find the grandest examples, with centuries-old buildings stained by tobacco stains and competing for space with car mechanics’ workshops.

This raises the question: Why are India’s cities becoming increasingly uninhabitable, despite spending hundreds of billions of dollars on a national facelift?

Despite high tariffs, weak private spending and stagnant manufacturing, India’s rapid growth has been driven largely by the Modi government’s focus on state-funded infrastructure upgrades.

In the past few years, India has built shining airportmulti-lane national highways and metro train networks. However, many cities rank at the bottom of the liveability index. Over the past year, frustration has reached a boiling point.

In Bangalore – known as India’s Silicon Valley for its many headquarters of IT companies and startups – citizens and billionaire entrepreneurs are openly angry because they are tired of the traffic jams and garbage heaps here.

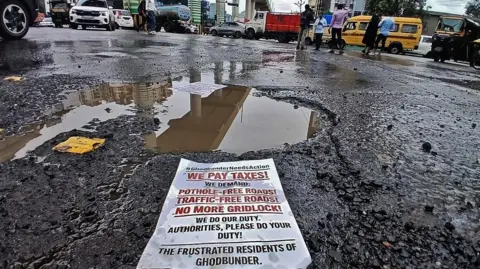

In the financial capital of Mumbai, clogged sewage pipes dumped rubbish onto flooded roads during the extended monsoon in a rare protest against a worsening pothole problem.

In Delhi’s annual winter of discontent, when toxic smog leaves children and the elderly breathless, doctors advise some to leave the city. Even footballer Lionel Messi’s visit this month was overshadowed by fans chanting against the capital’s poor air quality.

Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Hindustan Times via Getty ImagesSo why, unlike China during its boom years, has India’s rapid GDP growth not brought about the revitalization of dilapidated cities?

Why, for example, has Mumbai, which openly dreamed of becoming the Shanghai of the 1990s, been unable to realize this ambition?

“The root cause is historic – we don’t have a reliable governance model in our cities,” senior infrastructure expert Vinayak Chatterjee told the BBC.

“When the Indian Constitution was framed, it talked about devolution of power to central and state governments, but it did not envision that our cities would become so large that a separate governance structure would be required,” he said.

this world bank It is estimated that more than 500 million Indians, or nearly 40% of the country’s population, currently live in urban areas – a staggering number compared with 1960, when only 70 million Indians lived in cities.

In 1992, the 74th Amendment to the Constitution attempted to “finally give cities control of their own destiny.” Mr. Chatterjee said local bodies were given constitutional status and city governance was decentralized, but many provisions were never fully implemented.

“Vested interests will not allow bureaucrats and higher levels of government to devolve power and empower local agencies.”

This is in stark contrast to China, where mayors wield vast administrative powers and control city planning, infrastructure and even investment approvals.

Ramanath Jha, a distinguished fellow at the Observer Research Foundation think tank, said China follows a highly centralized planning model, but local governments have freedom to implement and are subject to centralized monitoring, with rewards and penalties.

“The state has strong directives in terms of the direction and specific goals that cities need to achieve,” Mr Jia said. Write.

Mayors of China’s major cities reportedly have strong backers and strong performance incentives in the Communist Party’s Supreme Council, making these positions “important stepping stones to further promotions.” Brookings Institution.

“How many names of mayors of India’s major cities do we know?” asked Mr Chatterjee.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesThe mayors and local councils that govern India’s cities are “the country’s weakest institutions, closest to citizens but tasked with solving the toughest problems,” said Ankur Beeson, author of “Waste,” a history of sanitation in India.

“They are absolutely emaciated – and have limited power in terms of raising revenue, appointing people, allocating funds. Instead, it’s the chief ministers of the states who act like super mayors and call the shots.”

There are also exceptional cases, such as the city of Surat after the plague outbreak in the 1990s, or Indore in Madhya Pradesh, where bureaucrats made revolutionary changes with the mandate of the political class.

“But these are exceptions to the rule – relying on the brilliance of individuals, rather than a system that will work long after the bureaucrats are gone,” Beeson said.

Beyond fragmented governance, India faces deeper challenges. The last census 15 years ago showed that 30% of the population was urban. Unofficially, nearly half of the country’s population is now thought to be urban and the next census will be postponed until 2026.

“But if you don’t have data on the extent and nature of urbanization, how do you start to solve the problem?” Mr Beeson asked.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesExperts say the data vacuum spelled out in the 74th Constitutional Amendment and the non-implementation of India’s Urban Transformation Framework reflect the weakening of India’s grassroots democracy.

“It is strange that there has not been an outcry in our city like there was against corruption a few years ago,” Mr. Chatterjee said.

Mr Beeson gave the example that India will have to go through a natural “realization cycle” Very smelly In London in 1858, it prompted the government to build a new sewage system for the city and marked the end of a severe cholera epidemic.

“Usually during events like this, when things reach a boiling point, the issue gains political traction.”