Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Jonathan HydeSoutheast Asia Correspondent, Mandalay, Myanmar

Jonathan Hyde/BBC

Jonathan Hyde/BBCOn a rugged stretch of land near the Irrawaddy River, retired Lieutenant General Tayza Kyaw, an aspiring member of parliament, tried to galvanize his audience with a speech promising a better life.

He is the candidate of the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) in Aung Mitazan constituency in Mandalay City, which is supported by the Myanmar military.

The crowd of 300 to 400 people clutched branded hats and flags issued to them, but soon faded in the afternoon heat, with some dozing off.

Children ran and played between the two rows of chairs. Many of the families are victims of the March earthquake that severely damaged Mandalay and its surrounding areas and want relief. As soon as the rally ended, they disappeared.

People in Myanmar got their first chance to vote in elections on Sunday since the military seized power in a coup nearly five years ago, sparking a devastating civil war.

But the poll has been repeatedly delayed by the ruling military junta and widely condemned as a sham. The most popular party, the National League for Democracy, has been dissolved and its leader Aung San Suu Kyi is in a secret prison.

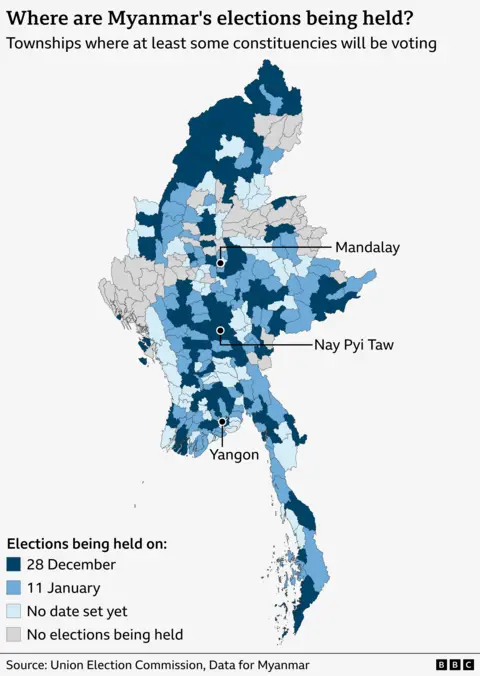

Voting will take place in three phases over a month but is not even possible in much of the country still torn by war. Even where voting was taking place, there was an atmosphere of fear and intimidation.

When the BBC tried to ask people at the Mandalay rally what they thought of the election, party officials told us not to. One man explained that they might say the wrong thing – they don’t know how to talk to reporters.

The large number of plainclothes military intelligence officers there helped explain their nervousness. In an authoritarian regime that makes it a crime to like Facebook pages critical of the election or use the word “revolution,” even these staunchly pro-military party activists worry about the consequences of allowing foreign journalists the opportunity to ask uncensored questions.

The same fear haunts the streets of Mandalay. At a market stall selling fresh river fish, customers refused to answer questions about their views on the election. “We have no choice, so we have to vote,” one person said. The fish seller chased us away. “You’re going to get me into trouble,” she said.

Only one woman was brave enough to speak out, but we needed to meet somewhere private, with no identity, just to hear her thoughts on the election.

“This election is a lie,” she said. “Everyone is afraid. Everyone has lost their humanity and freedom. So many people have died, been tortured or fled to other countries. How will things change if the military continues to rule the country?”

She said she would not vote but knew the decision would carry risks.

Lulu Luo/ BBC

Lulu Luo/ BBCMilitary authorities implemented a new law in July criminalizing “any speech, organization, incitement, protest or leafleting aimed at disrupting part of the electoral process.”

Earlier this month, Tayzar San, a doctor who was one of the first to organize protests against the 2021 coup, was among the first to be charged under the law for distributing leaflets calling for a boycott of the election. The junta offered a reward for information leading to his arrest.

In September, three young men in Yangon were each sentenced to 42 to 49 years in prison for posting stickers that placed bullets with ballot boxes.

Tezar San/Facebook

Tezar San/Facebook“Cooperate and suppress all those who harm the Federation,” a huge red poster appeared prominently above families and couples enjoying an afternoon stroll under the ancient red brick walls of Mandalay Palace.

In this menacing atmosphere, anything approaching a free vote is unthinkable.

However, military junta leader Min Aung Hlaing has been treading lightly of late. He seems confident that this extraordinary election, in which half the country did not vote at all, will give him the legitimacy he failed to gain during five disastrous years in power.

He even attended Christmas Mass at Yangon Cathedral and denounced “hatred and resentment between individuals” leading to “domination, oppression and violence in human communities”.

The man is accused by the United Nations and human rights groups of committing genocide against the Muslim Rohingya people, and his coup sparked a civil war that has killed 90,000 people, according to data analysis group ACLED.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesMin Aung Hlaing’s campaign strategy has received the full diplomatic support of China, which, strangely for a one-party state, has provided technical and financial support for this multi-party effort. The rest of Asia may also be reluctant to accept this.

His army, newly equipped with Chinese and Russian weapons, is regaining ground lost to various armed groups opposed to the coup over the past two years. He apparently hopes to include more of the regained territory in the third phase of elections at the end of January.

With Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy withdrawing, his United Democratic Party is almost certain to win. In the last free elections in 2020, the GND won only 6% of parliamentary seats.

Some observers note that Min Aung Hlaing is not popular even within his own regime or his own party, and his leadership qualities are in question. He is likely to remain president after the election, but his power will be somewhat diminished by the return of parliamentary politics, although most of the parties that won seats in the 2020 elections did not participate.

China clearly sees the election as an exit, a way for the military to escape the damaging deadlock caused by its misguided coup.

Even a short distance from Mandalay’s seemingly peaceful city life, the deep scars of Myanmar’s far-from-over civil war are clearly visible.

On the opposite bank of the Ayeyarwady River lies the spectacular temple complex of Mingun, once a popular tourist attraction. It’s a short drive along a riverside road, but for the past four years it, like much of the area around Mandalay, has been disputed territory, with the Volunteer People’s Defense Forces controlling many villages and launching ambushes on army convoys.

In order to reach Mingun we needed to pass several checkpoints. We sat in a tea shop with the local police commander to negotiate our passage.

He is a young man with a face that shows great pressure from work. He had a revolver stuck in the back of his trousers, and two even younger men – boys, perhaps – sitting next to him with military-style assault rifles, acting as his bodyguards.

Lulu Luo/ BBC

Lulu Luo/ BBCHe said he had to carry the weapons to move around the village.

His phone contained photos of his opponents: young men, dressed in rags, carrying various weapons that they might have smuggled from Myanmar’s border areas or obtained from dead soldiers and police officers. A group that calls itself the “Unicorn Guerrillas” is his most formidable opponent. He said they never entered into negotiations. “If we see each other, we always shoot. That’s the way it is.”

He added that most villages to his north would not hold elections. “Everyone here is taking a side in this conflict. It’s very complex and difficult. But no one is ready to compromise.”

An hour later we were told it was too dangerous to reach Mingun. PDF may not know you’re a journalist, he said.

Jonathan Hyde/BBC

Jonathan Hyde/BBCThe military who overthrew Myanmar’s young democracy, and who now want to remake its regime in a quasi-democratic guise, show no sign of compromise.

Asked about the shocking civilian casualties and airstrikes on schools and hospitals since the coup, General Thay Zak Kyaw placed the blame squarely on those who opposed the military takeover.

“They chose armed resistance,” he said. “Under the law, those who are aligned with the enemy cannot be considered people. So, they are just terrorists.”

People in Mandalay said that this election did not have the color and vitality of the 2020 election. There were few gatherings. Only five other parties are allowed to challenge the SDCP nationwide, and none has the resources and institutional support to do so. Turnout is not expected to be high.

Yet fearful of possible reprisals or simply exhausted by the civil war, many Myanmar people still go to the polls, regardless of how they feel about the election.

“We will vote, but not with our hearts,” one woman said.

Additional reporting by Luo Lulu