Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Gio Studio

Gio StudioFor the Indian film industry, 2025 is like returning to familiar ground.

The year before, female-led stories brief reinvention India’s global film image has brought acclaim and new attention. But last year, Bollywood’s violent, male-dominated action thrillers dominated the domestic box office and cultural conversation.

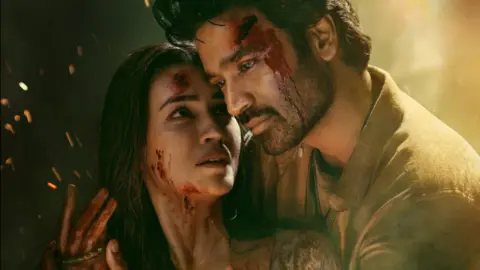

In the final weeks of 2025, Indian social media is abuzz with talk of a single giant: Dhurandhar, a spy thriller The story takes place against the backdrop of tense relations between India and Pakistan.

Filled with graphic violence and gangster politics, the film became the year’s decisive hit, cementing its place in a long line of aggressive, hypermasculine films driving popular discussion.

This trend is in stark contrast to 2024, when several films by women – Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine As Light, Shuchi Talati’s Girls Will Be Girls and Kiran Rao’s Laapataa Ladies – gained global attention and critical acclaim.

“What 2024 has established is that Indian female filmmakers are no longer marginal voices but leading global ones,” said film critic Mayank Shekhar, who called it a “pivotal moment” rather than a trend.

We hope that richer, more textured stories about women will grow in number and popularity. Instead, the top 10 grossing films of 2025 – five of them from Bollywood, which is small consolation for a Hindi film industry still struggling to get back on its feet after the pandemic – are dominated by larger-than-life superhero heroes, from the historical epic “Chhaava” to the action drama “War 2.” The only female-led film on the list is an exception: the Malayalam superhero film Lokah.

It’s not just action thrillers that put men at the center. The blockbuster romance “Cearra” tells the story of a troubled male rock star who ends up “saving” his partner as he battles Alzheimer’s disease. Even mythological spectacles like Kantala: Chapter One (Kannada) and Mahavatana Sinha (dubbed in multiple languages) double down on traditional male heroism.

The most talked-about movies this year feature mostly images of men performing pain, power and revenge at top volume.

T series movies

T series moviesAmong the top ten, one of the most controversial hits of the year is Tere Ishk Mein, which centers on an angry, volatile hero and a successful woman whose ambition is eclipsed by his obsessive love. Although criticized for romanticizing toxic masculinity, the film became actor Dhanush’s highest-grossing Hindi film, taking in more than 1.55 billion rupees ($17.26m, £12.77m) worldwide.

Another surprise hit was Ek Deewane Ki Deewaniyat, a relatively low-budget romantic drama starring: As the comments sayis “an obsessive lover who refuses to take “no” for an answer.”

Priyanka Basu, senior lecturer in performing arts at King’s College London, said 2024 gave us “a glimpse of what’s possible”.

She noted that Hindi cinema has historically marginalized female protagonists, adding that the male-centric industry has long had severe inequalities in casting, pay and opportunities.

“Just one year to change this is unrealistic. We need more years like this, and more stories that put women front and center,” she said.

Indian cinema, especially Bollywood, has a fascination with macho heroes that can be traced back to Amitabh Bachchan’s “angry young man” image in the 1970s.

Even the romantic era of a superstar like Shah Rukh Khan offered only a brief detour – one he later abandoned in favor of action blockbusters like “Pathan” and “Jhawan”.

The trend has also spread to streaming platforms — once seen as alternative spaces where female-centered storytelling could succeed.

A recent report by media research firm Ormax analyzed 338 Hindi shows on streaming platforms and found that action and crime thrillers (mostly male-led) currently account for 43% of all shows; female-led stories have dropped from 31% in 2022 to 12% in 2025.

“At some point, OTT (over-the-top, or streaming) platforms started chasing box office logic,” Mr. Shekhar said. “Today’s streaming reflects theatrical trends rather than challenging them.”

traveler movie

traveler movieTrade experts believe the shift reflects audience demand rather than a creative backsliding in the industry.

“Indian cinema has traditionally been male-dominated, but we also have female-centric classics like ‘Mother India’ and ‘Pakiza’,” said analyst Taran Adarsh.

He said the toxic accusations came from a “few critics” and would not change the film’s fate.

“At the end of the day, the only judgment that matters is the judgment of the audience,” he added.

But Delhi Crime 3 co-writer Anu Singh Choudhary thinks it’s too simplistic to blame everything on audience taste. Delhi Crime 3 is the third season of the Netflix thriller that highlights the issue of women trafficking through a feminist lens.

“Macho blockbusters have been around for a long time because they reflect a society that has always been patriarchal and male-dominated. Will that change overnight? No. But as the world order changes, so will our films,” she said.

There are also economic realities. Producers, distributors and exhibitors control a film’s screen count, marketing and visibility – which often depends on the box office receipts of its male star. Independent films and female-led films face an uphill battle, especially if they don’t have the backing of a big star.

Screenwriter Atika Chohan said today’s cinema is also going through a “period of performative, exaggerated misogyny”. His credits include the female-led films Chhapaak and Margarita With a Straw.

She believes this is partly a response to women’s demands for accountability during the MeToo movement of 2017-19.

While the movement exposed widespread abuse within the film industry, its impact was uneven. Some defendants faced temporary setbacks, but most returned to work and structural power imbalances largely remained.

“As long as these (hypermasculine) movies make money, they’re not going anywhere,” Ms. Chauhan said.

But as usual, signs of hope come mainly from smaller regional film industries and independent filmmakers.

Ms Chaudhry noted that India’s new generation of independent filmmakers were making “engaging, viable films” rather than “mass entertainers”.

Sharp independent films like “Sabar Bonda” and “Song of the Forgotten Tree” delve into complex social and political dimensions and tell sensitive stories of human relationships.

Telugu film Girlfriends tells the story of a woman in a toxic relationship who learns to free herself, while Bad Girls (Tamil) has been hailed as a successful coming-of-age drama told through a female lens.

Among Malayalam films, “Feminichi Fathima” (“Feminichi” is the social media distortion of “feminist”) uses humor to tell the story of a Muslim housewife’s silent rebellion against the patriarchy. On the streaming side, Shamsuddin was praised for capturing the day-to-day resilience and complexities of modern Muslim women.

“This is a quieter movement, starting from the margins,” Ms. Chaudhry said. “And it’s not going away.”