Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Grigor Artanissian and the investigative teamBBC News Russian

t.me/kotovayanora

t.me/kotovayanoraA Russian archaeologist detained in Poland is at the center of a heated debate over the role of museums and experts and their role in the Kremlin’s war propaganda.

Alexander Butyagin was arrested in Warsaw and is awaiting a decision by a Polish court on a request to extradite him to Ukraine.

Courts across Europe have so far been reluctant to invoke the European Convention on Human Rights to extradite Russians to Ukraine.

Butinkin’s case of disagreement.

As a senior scholar at the Hermitage, Russia’s largest art museum in St. Petersburg, he has led the museum’s expedition to the Mirmykion site in Crimea since 1999, long before Russia’s illegal seizure of Ukraine’s southern peninsula in 2014.

Supporters see his work as helping to preserve Crimea’s ancient heritage, but critics say he is tantamount to exploiting Russia’s occupation to plunder Ukrainian history.

Getty Images

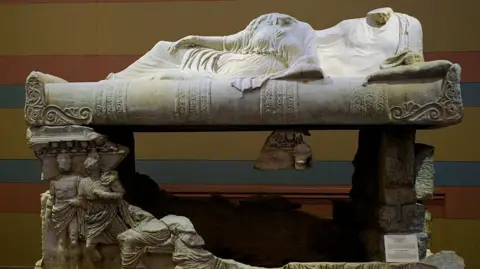

Getty ImagesThe history of Myrmekion dates back to the 6th century BC, when the ancient Greeks settled in Crimea and democracy was born in Athens.

Butyagin’s expedition discovered hundreds of ancient coins at the site, some from the time of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC.

His expeditions continued after Russia seized Crimea from Ukraine, and Ukrainian authorities opened criminal proceedings against him for working in Crimea without authorization.

In November 2024, he was placed on the wanted list, and in April 2025, a Kiev court ordered his arrest in absentia. Butyakin is accused of illegal excavation and “illegal partial destruction” of the archaeological complex.

According to Protocol II of the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, occupying authorities “shall prohibit and prevent” any archaeological excavations, with only a few rare exceptions.

Poland and Ukraine are both parties to the protocol, while Russia is not.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesEvelina Kravchenko, a senior researcher at the Institute of Archeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, said that regardless of ethics, excavations without permission and under conditions of armed conflict amount to destruction.

Klitschko said Butyakin “violated the Hague Convention and all his problems stem from that.” Klitschko’s committee issued permits to Russian archaeologists to work in Crimea before it was annexed.

Butyakin told Russian media last year that he was “just doing the work we have dedicated our lives to” and that his main goal was to protect the monument.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Hermitage press office insisted that Butyakin’s work complied with all international legal and ethical norms “regardless of geopolitical circumstances.”

A senior archaeologist at the museum told the BBC that Butyakin was following the only path that Russian archaeologists working in Crimea could take.

“Russian archaeologists do not have the opportunity to obtain permission from Ukraine if they want to continue research, but must obtain permission from the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation,” said the academic, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to comment on the case.

Some Ukrainian sources have also accused Butyakin of “looting” items by bringing them to Russia, although these charges are not part of the Ukrainian case.

Both archaeologists and the Hermitage Museum insist that all their finds remain in Crimea, as they were transferred to the East Crimean Museum in Kerch. They believe that the objects can only be temporarily transferred to Russia for restoration or as loan for exhibitions.

However, this also violates Ukrainian law, as all finds must go to the Ukrainian Museum Fund. Under the terms of Russia’s illegal annexation, the collections of the East Crimean Museum instead became part of the Russian Museum Fund.

Since the war began, some European courts have rejected Ukraine’s requests to extradite Russians, citing potential risks under the European Convention, which bans politically motivated persecution, violations of fair trial rights and torture and inhumane treatment of detainees.

Gleb Bogusz, a researcher at the Institute of International Peace and Security Law at the University of Cologne, said that even if a Polish court does find sufficient grounds to extradite Butyakin, it may not go ahead.

Last June, Denmark’s Supreme Court ruled against extraditing to Ukraine a Russian national suspected of spying for Moscow.

Gleb Bogush said the Russian government and its officials, not Butyakin, were primarily responsible for excavations in Crimea because the decision on whether to continue the Hermitage expedition did not lie with archaeologists.

A senior Hermitage employee told the BBC that “an on-site archaeologist cannot be a citizen of the world; he deals with officials, obtains permissions and has to find funding and volunteers”.

Butyakin has attracted support not only from the Kremlin but also from Russians opposed to Putin and the war.

“The accusations against him are ridiculous,” said Arseny Vesnin, an exiled journalist and historian. He said Butyakin ensured the protection and preservation of the sites he was excavating.

Others believe that if Russian archaeologists refused to work in Crimea, artifacts would be looted by criminals and sold on the black market.

Samuel Andrew Hardy, a leading British criminologist who specializes in the protection of cultural property in conflict zones, said this did not justify their actions.

He argued that official excavations did not always prevent criminal excavations from occurring. Some looters target sites that have already been excavated.

Hadi said all Butyakin’s supporters are doing is arguing that Russia should ultimately be allowed to continue doing what it wants, regardless of war.